Das Monument

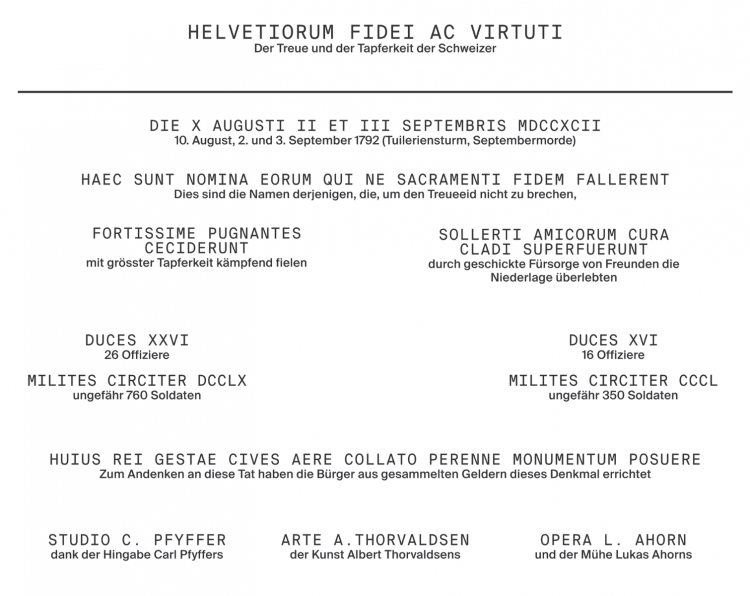

Auf Latein, damit es alle verstehen — Der Titel ist die Botschaft: Die Treue und die Tapferkeit der Schweizergarde sind zu loben. «Helvetier» steht für jene Männer, die 300 Jahren lang aus der Eidgenossenschaft, durch private Militärunternehmer gestellt, Solddienst für die französischen Könige leisteten.

Mehr als 500’000 Söldner waren es vom 15. bis 18. Jahrhundert, 60 Prozent kehrten nicht mehr heim. 1792 brach dieser lukrative Handel für das Soldpatriziat ein. Die Inschrift des Denkmals listet allein die Namen der Offiziere auf.

Am 10. August und 2. + 3. September getötete Offiziere und Schweizergardisten

«Korrekt wiedergegeben ist in der Inschrift des Löwendenkmals die Zahl der getöteten Offiziere mit 26, die Zahl der getöteten Soldaten hingegen ist mit ‹etwa 760› eine Legende und um die Hälfte zu verringern! […]

Am 8. August 1792 bestand das Garderegiment aus etwa 1500 Mann. Fast 300 Mann waren zum Schutz von Kasernen, Schlössern oder auf andere Pariser Posten detachiert. 300 weitere waren in die Normandie geschickt worden. Nur etwa zwei Gardekompanien bewachten die Tuilerien. […]

In der Nacht vom 9. auf den 10. August verteilten sich 800 bis 900 Schweizer – wenn man die Freiwilligen, die zu Hilfe gekommen waren, und einige französische Adlige, die die Schweizer Uniformen angezogen hatten, mitzählt – auf etwa zwanzig Posten, ständig in Alarmbereitschaft, in Erwartung der letzten Schlacht. […]

Der Angriff auf die Tuilerien am 10. August war nicht improvisiert, sondern über mehrere Wochen sorgfältig vorbereitet worden. Die Jakobiner hatten begriffen, dass es sinnlos war, auf friedlichem Weg zur Absetzung des Königs aufzurufen. […]

Der Tuilerienpalast war keine Festung wie die Bastille. Man musste sich 35’000 bewaffneten Aufständischen stellen. Um die Mittagszeit kämpften im Palast 400 bis 450 Schweizer, Stufe um Stufe auf der grossen Treppe des Hofes. Einer gegen Hundert. Die letzten Schweizer kämpften bis 16 Uhr. Widerstand war zwecklos. Alles endete mit einem allgemeinen ‹Rette sich, wer kann›. […]

Der Schweizergardist verkörperte als Hüter des Königreichs die monarchische Macht. Seine Person trat an diesem Tag an die Stelle des Königs, den der Hass des Volkes noch nicht hatte zu Fall bringen können. Der Widerstand der königstreuen Schweizer, die als ‹an die Bourbonen verkauft› dargestellt wurden, löste eine wilde Wut aus. Das bis in die Nacht hinein dauernde Gemetzel war der Massstab aller aufgestauten Ressentiments. […]

Gemäss Unterlagen aus Archiven und Bibliotheken wurden von den 39 Schweizer Offizieren, die in den Tuilerien anwesend waren, am 10. August 15 getötet und im September 11 massakriert. Vom Schweizergarderegiment (rund 1500 Mann) haben gegen 1200 überlebt. Das heisst, am 10. August 1792 und während der September-Massaker wurden in Paris 300 bis 350 Offiziere und Schweizergardisten getötet.

Auf der Seite der Aufständischen werden in den französischen Quellen in Paris «376 victimes» (Tote und Verwundete) festgehalten.»

Exzerpt von Jürg Stadelmann aus: Alain-Jacques Tornare, «Ein epochales Ereignis zwischen Mythos und Realität», in: In die Höhle des Löwen – 200 Jahre Löwendenkmal Luzern, 2021.

Bossard-Borner Heidi, Der Mann hinter dem Löwendenkmal. Carl Pfyffer von Altishofen und seine Zeit. In: Büro für Geschichte, Kultur und Zeitgeschehen / Stadt Luzern (Hrsg.), In die Höhle des Löwen. 200 Jahre Löwendenkmal Luzern, Luzern 2021, S. 93–104 .

Castelberg Marcus, Vom Stehen und Gehen – ein patrizischer Nachkomme sinniert und staunt. In: Büro für Geschichte, Kultur und Zeitgeschehen / Stadt Luzern (Hrsg.), In die Höhle des Löwen. 200 Jahre Löwendenkmal Luzern, Luzern 2021, S. 275–276.

Fuhrer Hans Rudolf, Eyer Robert-Peter, Clerc Philippe, Schweizer in “Fremden Diensten”: verherrlicht und verurteilt. 2. Auflage, Zürich 2006.

Hitz Benjamin, Kämpfen um Sold: Eine Alltags- und Sozialgeschichte Schweizerischer Söldner in der Frühen Neuzeit, Köln u.a. 2015.

Holenstein André, Kury Patrick, Schulz Kristina, Schweizer Migrationsgeschichte. Von den Anfängen bis zur Gegenwart, Baden 2018.

Höchner Marc, Das Söldnerwesen in der Zentralschweiz 1500–1800 als Migrationsbewegung. In: Der Geschichtsfreund 2014 (167), S. 11–29.

Huber Cécile, Wenn Menschen zu «Betriebsressourcen» werden. Rekrutierung, Ausbildung, Entlöhnung und Entlassung von Söldnern. Eine Spurensuche in Frankreich und Luzern. In: Büro für Geschichte, Kultur und Zeitgeschehen / Stadt Luzern (Hrsg.), In die Höhle des Löwen. 200 Jahre Löwendenkmal Luzern, Luzern 2021, S. 63-74.

Kälin Urs, Die fremden Dienste in gesellschaftsgeschichtlicher Perspektive. Das Innerschweizer Militärunternehmertum im 18. Jahrhundert. In: Furrer Norbert et al. (Hrsg.), Gente ferocissima. Solddienst und Gesellschaft in der Schweiz (15.—19. Jahrhundert), S. 279–287.

Messmer Kurt, Hoppe Peter, Luzerner Patriziat. Sozial- und wirtschaftsgeschichtliche Studien zur Entstehung und Entwicklung im 16. und 17. Jahrhundert, Luzern/München 1976.

Rogger Philippe, Ende eines einträglichen Geschäfts. Die Strategie des «Obenbleibens» der Militärunternehmerfamilie Pfyffer um 1800. In: Büro für Geschichte, Kultur und Zeitgeschehen / Stadt Luzern (Hrsg.), In die Höhle des Löwen. 200 Jahre Löwendenkmal Luzern, Luzern 2021, S. 77–90.

Rogger Philippe / Schmid Regula (Hrsg.), Miliz oder Söldner? Wehrpflicht und Solddienst in Stadt, Republik und Fürstenstaat (13.–18. Jahrhundert), Paderborn, 2019.

Schiess Giulia, Stadelmann Jürg, Meier Ruedi, Vom Umgang mit der vornehmen Herkunft. Wie denken die Nachkommen von Luzerner Patriziern über das Erbe der Geschichte? Eine Annäherung. In: Büro für Geschichte, Kultur und Zeitgeschehen, Stadt Luzern (Hrsg.), In die Höhle des Löwen. 200 Jahre Löwendenkmal Luzern, Luzern 2021, S. 259–274.

Tornare Alain-Jacques, Ein epochales Ereignis zwischen Mythos und Realität. Der Sommer 1792, wie er in Frankreich und in der Schweiz wahrgenommen wird. In: Büro für Geschichte, Kultur und Zeitgeschehen / Stadt Luzern (Hrsg.), In die Höhle des Löwen. 200 Jahre Löwendenkmal Luzern, Luzern 2021, S. 33–52.

Von Greyerz Kaspar, Holenstein André, Würgler Andreas (Hrsg.), Soldgeschäfte, Klientelismus, Korruption in der Frühen Neuzeit. Zum Soldunternehmertum der Familie Zurlauben im schweizerischen und europäischen Kontext, Göttingen 2018.

HLS, Denkmäler:

https://hls-dhs-dss.ch/de/articles/024482/2010-04-15/

HLS, Fremde Dienste:

https://hls-dhs-dss.ch/de/articles/008608/2017-12-08/

HLS, Schweizergarde:

https://hls-dhs-dss.ch/de/articles/008623/2007-06-29/

HLS, Reisläufer:

https://hls-dhs-dss.ch/de/articles/008607/2011-05-19/

HLS, Militärunternehmer:

https://hls-dhs-dss.ch/de/articles/024643/2009-11-10/

HLS, Patriziat:

https://hls-dhs-dss.ch/de/articles/016374/2010-09-27/

HLS, Patrizische Orte:

https://hls-dhs-dss.ch/de/articles/026422/2010-09-27/

Soldallianz 1521 Frankreich und Luzern:

https://staatsarchiv.lu.ch/schaufenster/quellen/Soldallianz

Swissinfo, Heimweh:

https://www.swissinfo.ch/ger/blog-schweizerisches-nationalmuseum_heimweh-nach-den-bergen/45267482

Abb. 1: Schweizerisches Nationalmuseum, LM-156092, Bauern und Landsknechte, XVI. Jahrhundert, Carl Röchling, um 1900.

Abb. 2: Modell des Löwendenkmals von Bertel Thorvaldsen von 1819 im Historischen Museum Luzern, Fotografin Susanne Stauss, 2021.

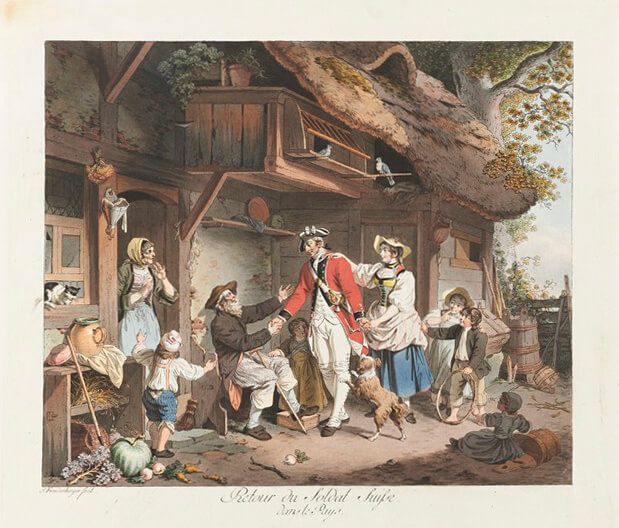

Abb. 3: Schweizerische Nationalbibliothek, GS-GUGE-FREUDENBERGER-C-32, Freudenberger Sigmund, Retour du Soldat Suisse dans le Pays, 1778–1780.

Abb. 4: Fotografin Giulia Schiess, 2020

Abb. 5: Bild meierkolb

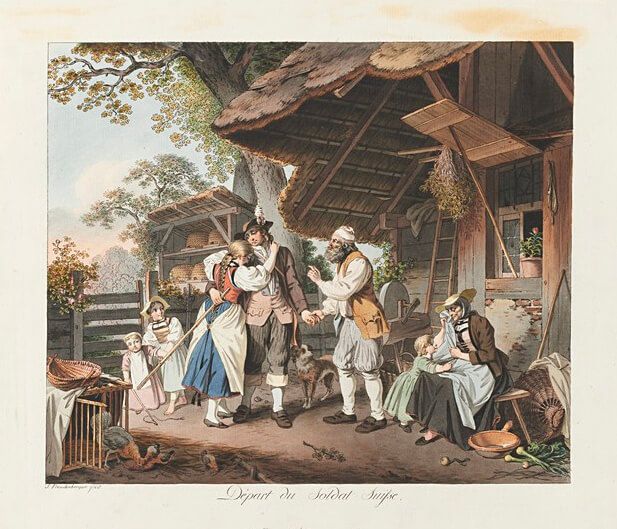

Abb. 6: Schweizerische Nationalbibliothek, GS-GUGE-FREUDENBERGER-C-31, Freudenberger Sigmund, Départ du Soldat Suisse, 1778–1780.

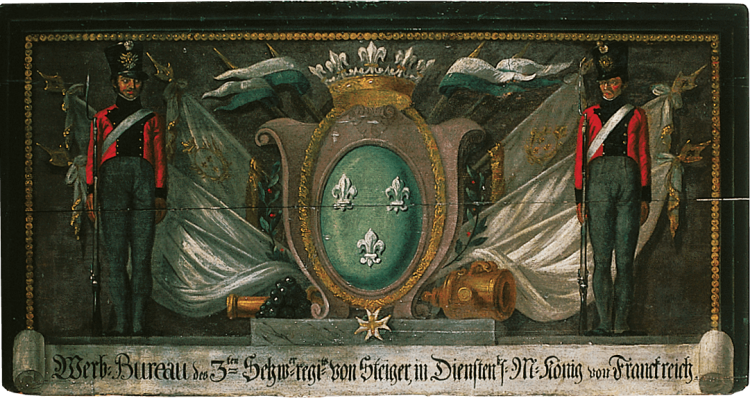

Abb. 7: Museum Burg Zug, Inventarnummer 2024, Tafel zur Werbung von Söldnern für das 3. Schweizer Linienregiment von Steiger, Maler unbekannt, vermutlich 1818–1830, Tempera auf Holz, 80.00 x 152.0 x 5.0 cm.

Bildquellennachweis

Wir haben die Abklärung der Bildrechte nach bestem Wissen und Gewissen vorgenommen. Sollten unsere Bildnachweise unvollständig sein, bitten wir um Nachsicht und sind für jeden Hinweis dankbar.